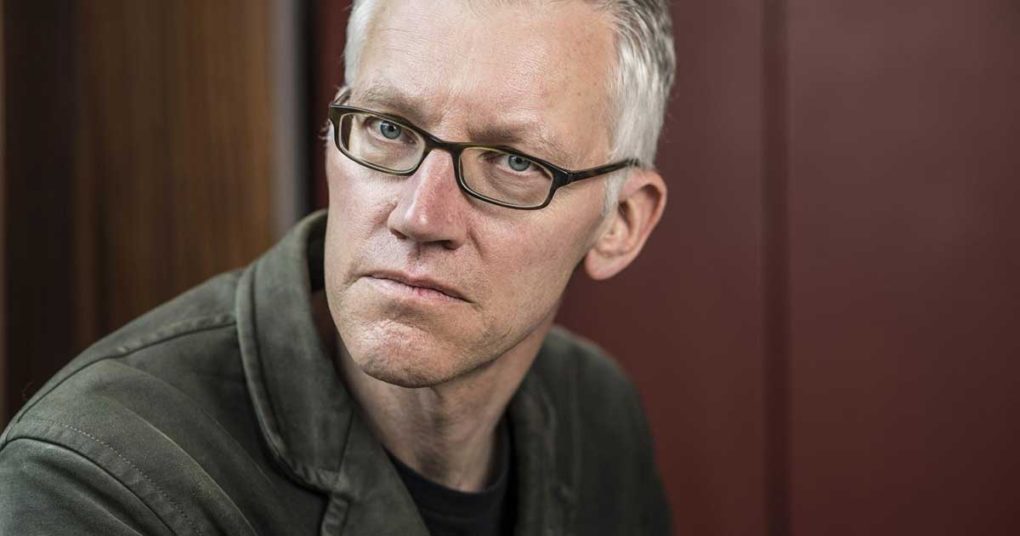

Dominion, the latest book by the popular historian Tom Holland (the author of Rubicon, Persian Fire and In the Shadow of the Sword), was published in September. Given the success of Holland’s previous books, many history buffs will be including Dominion on their Christmas wish list.

Holland made his name exploring broad historical periods like the fall of Roman Republic or the rise of Islam, but Dominion focuses on a subject which many historians steer clear of: the role of Christianity in shaping Western civilisation, and shaping it for the better.

Considering the various upheavals (both political and social) currently underway in the West, it is a worthy topic, especially given that Holland is himself an atheist. Though raised in the Church of England, the author’s Christian faith waned from childhood onwards and he found himself being drawn towards classical history, including the Greek gods.

Like many intellectuals, he initially accepted the thesis of Edward Gibbon that the triumph of Christianity during the Roman Empire’s dying days had ushered in a more superstitious and credulous era. Gibbon’s views were not shared by most Europeans when he was writing in the late eighteenth century, but few within Europe’s cultural elite would criticise them now. All religion is deemed to be backward, and the fact that Christianity has played a formative role in shaping the culture of every European nation is seldom reflected upon.

As a non-believer, Holland’s interest in writing about this topic is not motivated by a desire to bring people into the Church. Over the course of several decades, he became an authority on ancient Greek and ancient Roman history. Fascinated though he was with them, there were parts of this pre-Christian culture which the historian could not embrace, in particular, the extraordinary brutality which was considered normal in such societies, and which their religions condoned.

“The more years, I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, the more alien I increasingly found it,” Holland writes.

“The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more.

“It was not just the extremes of callousness that unsettled me, but the complete lack of any sense that the poor or the weak might have the slightest intrinsic value.”

The examples of the abuse of the weak and powerless are widely-known among anyone familiar with Greco-Roman history: public execution of slaves, gladiatorial combat for the amusement of spectators, the widespread abandonment of baby girls in refuse dumps, and so on. Not all of this was stamped out by Christianity immediately (the continuation of slavery being an obvious and sad example), but over time, the moral principles of Christianity became so deeply embedded within European societies that the greatest abuses of ancient Rome and Greece became unthinkable.

Without the conversion of Europe, this could not have happened. As Holland explains, there was nothing in Greco-Roman polytheism which would give pause to a Roman nobleman considering raping his slave girl, or to a general about to order his legionaries to annihilate a defeated tribe.

Ancient Athens is still renowned for the high-quality of its political philosophy, but though the gods would intervene in all manner of earthy affairs, they were not likely to intervene in defence of those at the bottom of the societal hierarchy. These immortals, Holland adds, “were held to be simultaneously whimsical and purposeful, amoral and sternly moral, arbitrary and wholly just.”

As Holland explains at length, the Jewish people played a vital role in fostering the understanding of a different, monotheistic, God whose actions could – for the most part – be understood. Holland’s tracing of the historical evolution of the Western mind inevitably brings us to Jesus.

Curiously, the actual life of Christ is not dwelt upon here, but as the author states early on, this is not a history of Christianity, nor a biography of its central figure. The crucifixion does however play a central role in the cultural shift Holland is describing, and he points this out again and again. Death on the cross was a punishment only thought suitable for slaves.

In Greece and Rome and other pagan societies throughout the world, the gods were enormously powerful, and in these societies, strength and power were lauded, even when they went hand-in-hand with cruelty. The idea of God becoming a man and willingly suffering this kind of torture and death ran completely contrary to the ideas of paganism. It presented a clear challenge to the divisions that had previously separated the powerless from the powerful. Furthermore, the mission of St. Paul and the other followers of Jesus was clearly universal.

Where before, one people would have many gods, this God was to be made known to all people: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” That Christian message would soon be spread across the Roman Empire to the point where Christianity would quickly replace paganism as the dominant religion, with the result that many of the worst practices of old went from being common, to being frowned upon, and then to becoming unthinkable.

The story of Western civilisation did not end then, of course, and Holland’s book traces its evolution up to the present day, taking in all manner of figures, groups and movements: Origen, St Martin of Tours, St Augustine, Muhammad, Charlemagne, the Albigensian Crusade, the persecution of the Hussites, Martin Luther, Voltaire, the Enlightenment, Charles Darwin and much, much more besides.

Holland’s analysis of how the nihilistic German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche influenced modern thought is especially interesting. Modern-day atheists often stress that they still belief in concepts such as “human rights” or “human dignity,” which are frequently presented as having evolved out of nothing.

“We are all twenty-first century people,” Holland quotes Richard Dawkins as saying, “and we subscribe to a pretty widespread consensus of what is right and wrong.”

In his rejection of the Christianity which he was reared in, Nietzsche made clear that he and others like him could not engage in such wishful thinking: “When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet.”

Not that he wanted to keep hold of it.

Nietzsche admired the pagan philosophy of exalting strength and crushing weakness, and wished to recreate a world like that which existed “in the days before mankind grew ashamed of its cruelty.” The waning belief in Christianity – already obvious in many advanced European societies during Nietzsche’s lifetime – had done much to reduce that shame, but more was to follow.

When he died in 1900, Nietzsche probably could not have anticipated just how soon Germany would revert to a pagan moral ethos, one which would be made far worse due to the progress which had been made in military and scientific technology during the previous two millennia.

There is much to admire in this book, not least the fact that an irreligious historian has taken such time to examine Christianity’s positive role in creating a kinder, gentler and more loving world than could otherwise have existed.

Holland is a terrific writer, and one who is enormously authoritative in his analysis of history. But in meandering through such an enormous period of history encompassing so many important subjects, he has ended up trying to do too much.

At 525 pages, Dominion feels very long indeed, and some of the links that Holland sees between Christianity and other tendencies in modern Western societies seem tenuous at best. This does not reflect on the author: any one volume effort to describe the Christian roots of Western civilisation would probably be doomed to failure also.

Earlier this year, the conservative Christian writer Samuel Gregg tried to accomplish something somewhat similar in Reason, Faith and the Struggle for Western Civilization. This book was only half as long as Dominion, but still suffered from some of the same flaws.

Conversely, there are other important issues that Holland could have addressed and did not. Holland is right to highlight how unwanted and physically imperfect children were either put to death or abandoned in pagan societies like pre-Christian Rome. In its insistence on the dignity of every innocent life, the newly ascendant Christianity firmly stamped these practices out.

But it did more than condemn infanticide or abandonment. The sociologist Rodney Stark achieved some renown in the 1990s when he wrote The Rise of Christianity, which looked at how a small sect had multiplied so rapidly to become the majority religion of the Roman Empire within three centuries.

However grisly and unsafe the technique was, Stark wrote that abortion was commonplace in pre-Christian Rome. The steadfast refusal of the Catholic Church to accept the killing of children – born or unborn, wanted or not – played an important role in causing the number of Christians to grow rapidly.

Somewhat ironically given the dogmatic attitude of modern feminists, this also made the new religion more attractive to Roman women. Thus, the number of converts grew.

In addition to condemning the slaughter of the young, Christianity also placed a much greater importance on caring for the sick and the aged. Contrast this with the present-day state of what is still, in some respects, Christendom. Abortion has been readily available in most Western societies for several generations now. Abortion on the grounds of disability is rampant. People with conditions like Down’s Syndrome are being systematically erased. The morals of Sparta are no longer so foreign.

Several countries have legalised euthanasia as well, and horrific stories about patients being involuntarily dispatched are now being reported in the Netherlands and elsewhere. In Europe, a human being’s survival is, once again, dependent on the will of those who are stronger and more powerful.

Tom Holland recoils from the worst abuses of the pagan societies he has studied but has nothing to say about how closely we are beginning to mirror them. Alas, a liberal atheist was never likely to challenge this regression into savagery.

All that being said, this is an important book. Hopefully, it will be the start of a critical re-evaluation of how the most humane and advanced civilisation in the world came into existence. It could not have been published at a more important time, when Europeans need to re-familiarise ourselves with what the author rightly calls the greatest story ever told.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw works in an international consulting firm, based in Dublin, and is a regular contributor to Position Papers.