The Church does not exist to condemn people but to help them encounter “the visceral love of God’s mercy,” says Pope Francis in a new book out Jan. 12, an exploration of the defining theme of Francis’ papacy that is also a gentle response to his critics.

The 150-page book – published in eighty-six countries and twenty languages – is in reality an extended conversation over four hours last summer with veteran Vatican journalist Andrea Tornielli, in which he explains how he has come to center his ministry and now his papacy on God’s constant readiness to heal and forgive.

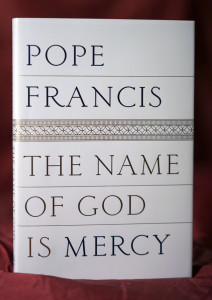

“The Name Of God Is Mercy” (Random House, $26) was launched in Rome at a presentation this week by one of the Church’s most senior cardinals, a Chinese prisoner serving a 20-year term in an Italian prison, and the Oscar-winning Italian comic actor, Roberto Benigni, who joked that “only this Pope” could have organized his book launch in this way.

The prisoner, 30-year-old Zhang Agostino Jianqing, who immigrated to Italy in his youth, told a poignant story of being condemned to twenty years in prison for an unspecified “error” he committed at the age of 19. While in prison, he resolved to change his life and was received into the Church, taking the baptismal name of Augustine. Thanking Pope Francis, whom he met Monday night, for his attention to prisoners, Jianqing said he wanted his story to witness to “how God’s mercy changed my life.”

The book breaks no new ground doctrinally, and Francis is at pains to point out that his emphasis on God’s mercy builds on the teaching of his predecessors since Pope St. John XXIII, who are quoted throughout the text.

Yet the book is also striking in its directness and informality, as well as its personal stories of how Francis has experienced mercy in his personal life, his priestly ministry – above all, in the confessional – and in his spirituality. The pope says, for example, that he can read his own life in the light of Chapter 16 of the prophet Ezekiel, in which “shame is a grace: when one feels the mercy of God, he feels a great shame for himself and his sin.” And he recalls the impact on him of the death of the confessor he met when he was 17. When Father Carlos Duarte Ibarra died a year later of leukemia, “I cried a lot that night, really a lot, and hid in my room,” he recalls. “I had lost a person who helped me feel the mercy of God.”

When Tornielli asks, “Can there be opposition between truth and mercy, or between doctrine and mercy?” Francis’ answer is that mercy is doctrine, for it is the truth about God – “God’s identity card.” Mercy is not an emphasis or an aspect of the divine but who God is; it is “the divine attitude which embraces, it is God giving himself to us, accepting us, and bowing to forgive.” Mercy, he says, “is real; it is the first attribute of God. Theological reflections on doctrine and mercy may then follow, but let us not forget that mercy is doctrine.”

Repeating a contrast he used in a homily to the cardinals in February last year, Francis critiques the approach of the “scholars of the law” who criticize Jesus in the name of doctrine, an approach he says is “repeated throughout the long history of the Church.” Whereas the “logic of the law” is driven by a fear of losing the just and the saved, “the logic of God” is shown in Jesus’ desire to save the lost and sinners. The logic of the law leads to the expulsion of the leper in order to protect the healthy from contamination; God’s logic is shown in Jesus entering into contact with the leper, touching him and seeking his integration. “In so doing, he teaches us what to do, which logic to follow, when faced with people who suffer physically and spiritually.”

But the desire to change – however small and tentative – has to be there. Because God is misericordis – which the Pope defines as “opening one’s heart to wretchedness” – God’s mercy can only be received by people who acknowledge their wretchedness. “If you don’t recognize yourself as a sinner it means you don’t want to receive [mercy],” the Pope says, adding: “This is a narcissistic illness.”

While the Church “condemns sin because it has to relay the truth,” he says elsewhere, “it embraces the sinner who recognizes himself as such.”

But the Church has to look for opportunities. In order to help people encounter God’s mercy, the Church has to go out from itself and seek people out, offering them new possibilities, rather than focus on protecting the flock. “As a confessor, even when I have found myself before a locked door, I have always tried to find a crack, just a tiny opening, so that I can pry open that door and grant forgiveness and mercy,” Francis says.

The Pope expresses his hope that the Jubilee Year of Mercy, which opened before Christmas, “will serve to reveal the Church’s deeply maternal and merciful side, a Church that goes forth toward those who are ‘wounded’, who are in need of an attentive ear, understanding, forgiveness and love.”

—

About the Author: Austen Ivereigh

Austen Ivereigh is the author of The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope (Henry Holt, $30). This article was originally published in OSV Newsweekly and is reprinted with the kind permission of Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.